Thinking about imperialism with Hannah Arendt

Quite possibly, if you think about Hannah Arendt, the first thing that comes to mind is not her work on imperialism. Her most famous works are probably The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) and Eichmann in Jerusalem (1963). The latter, published in the New Yorker as a series of reports on her observations of the trial of Adolf Eichmann, caused a furore upon its publication and subsequently, for rehearsing what has been read as a narrative of blaming the victims. Arendt is and was a controversial figure and thinker in more than one way – not least, for instance, in the fact that she opposed desegregation of schools in the United States in the 1950s. Feminists eager to find something to further feminist causes in so well-respected a woman political scientist and philosopher might be disappointed: the ‘woman question’, so Arendt, never interested her in particular. All the same, Arendt’s writing remains full of food for thought, to which thinkers seem to return again and again. In discussions about the migrations to Europe of 2015, for instance, scholars would once more call on her as one of the key thinkers on questions of the ‘refugee’ and the ‘stateless’ person; and her formulation of ‘the right to have rights’ is still cited often.

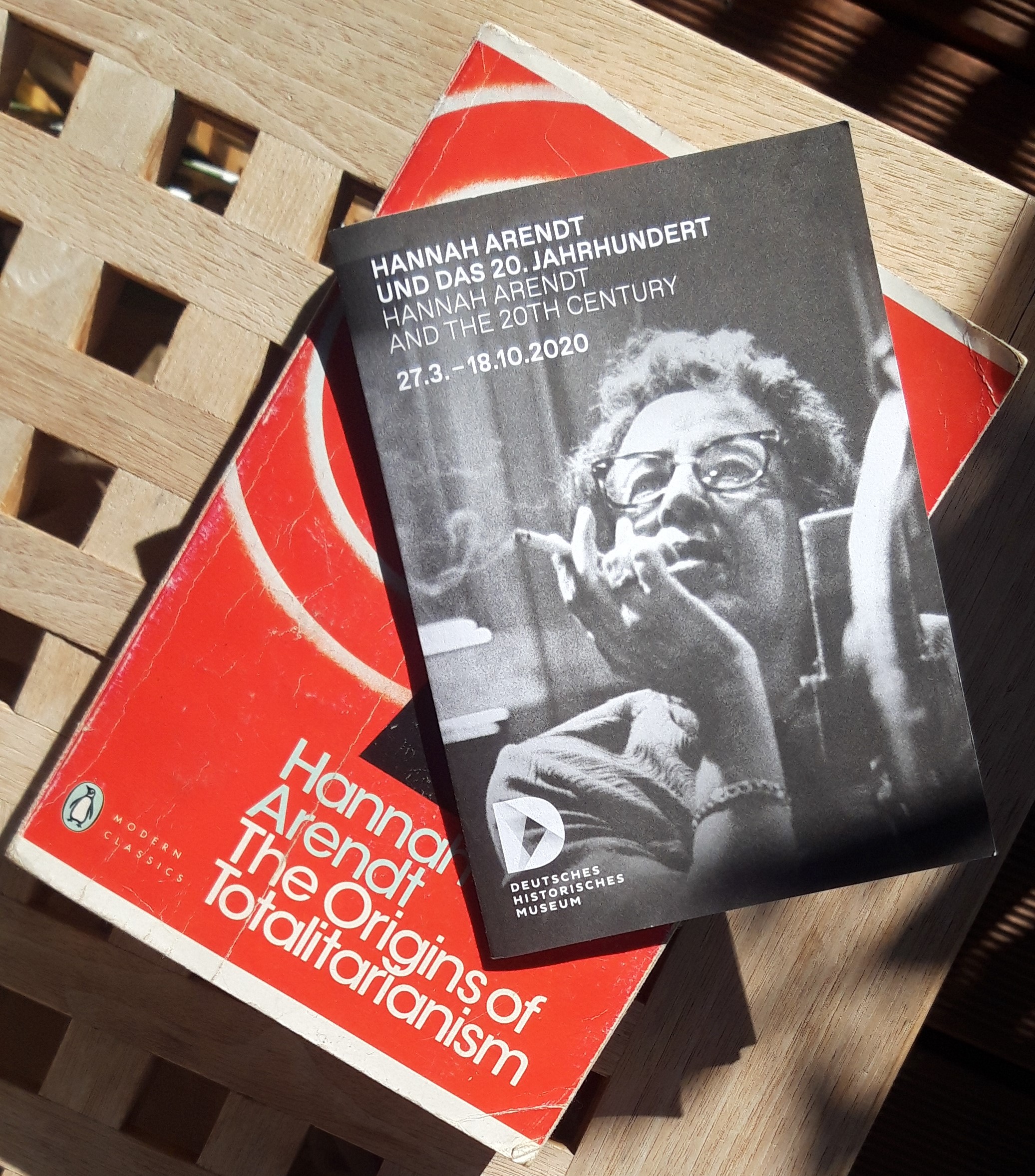

There is, currently and running until the 18th of October 2020, an exhibition on at the Deutsches Historisches Museum (German Historical Museum) in Berlin on Hannah Arendt and the 20th Century. The exhibit does well to lend an overview of the life and works of the woman who was born in 1906 near Hannover, who studied philosophy under Martin Heidegger, who was forced to flee from national socialism to Paris in 1933, and onward to the United States in 1941, where she would become a citizen in 1951. It includes wonderful footage of her chain-smoking her way through interviews – and a moment in which she expresses her view that it doesn’t look good on women to give orders – and less riveting moments such as the inclusion of a fur-coat and jewellery that once belonged to her.

My interest in the exhibition was roused by recently having read The Origins of Totalitarianism, which, unfortunately for me, made up a relatively small part of the exhibition. It is in the second part of this hefty volume – in between sections on antisemitism and totalitarianism – that Arendt discusses imperialism. She does so because the era of overseas expansionism that gained momentum in the 1880s forms, for her, a constitutive moment in the building of the discourses and political instruments that would make the ‘totalitarianism’ of the Nazis and the Soviets possible. As with several of her other views, there is plenty to take issue with here, but there are also some intriguing observations that might lend themselves to productive further consideration. I would have liked to see the exhibition contextualising this facet of Arendt’s work for its relevance to, or dissonance with, our present moment.

In Arendt’s take, imperialism bequeathed to totalitarianism two tools, without which the Nazi and Communist movements that followed would have been unimaginable: they are government by bureaucracy and rule by race. British imperialism in India, as she tells it, produced an administration in and of the subcontinent that ruled by reports, repressing any efforts at revolt through “administrative massacres”. The author par excellence of this is Rudyard Kipling, who gave us not only the infamous poem “The White Man’s Burden”, but also the novel of the British India Survey, Kim, which charts, under the guise of an adventure-espionage tale, the gathering of cartographic and ethnographic data in order to better administer colonised territories – i.e. to gather bureaucratic fodder.

Race as an instrument of rule was gifted, following Arendt, by the outlier example of South Africa. South Africa is an outlier here because it hadn’t been intended for settlement, bearing until the discovery of diamonds in Kimberly only instrumental value as a port of call on the way to India. The terrain was too ungenerous and the indigenous population too numerous to make of it an attractive place for European colonisers to stay. But that is precisely what the ‘Boers’, the descendants of early Dutch arrivals to the Cape (around today’s Cape Town) did. The Boers, in Arendt’s rendition, set up the first true race society, and as she would have it, when they lost the South African War against the British, they nonetheless won the consent of Europeans to that race society. For Arendt, the Nazis would learn from such examples on the African continent – for instance, that a race ideology could trump the profit motive, as the Boers had shown repeatedly a willingness to forego economic gain in the name of maintaining the structures of white supremacy.

The author she draws on in her discussion of imperialism in Africa is Joseph Conrad, and more specifically Heart of Darkness – she notes, incidentally, that the real-life inspiration for the central figure of Kurtz in that novella may well have been the German colonist and génocidaire, Carl Peters. There are some mortifying moments in Arendt’s discussion of Heart of Darkness. Conrad’s novella is famously problematic, and it is perhaps simultaneously paradoxical and not unusual that it is in the name of understanding racism that she imbibes Conrad’s racist representation of African peoples as somehow accurate. As she puts it, it “is the most illuminating work on actual race experience in Africa”. Needless to say, it really isn’t.

What The Origins of Totalitarianism can serve to give, in my view, is a springboard for thinking through how racial logics and discourses circulate and are instrumentalised in different contexts. This can still be important to understanding how racism works today. Even as Arendt credits the South African Boers with developing the first genuine race society, conceiving of one people’s essential, naturalised and racial superiority over another begins much earlier than that; she places the origins of race-thinking in France in the 18th century. Through what is called the boomerang effect of colonialism, discourses or approaches that had proved useful in the colonies found their way back to Europe, and were reincarnated to different ends, or in different forms. Logics of racism are unlikely to emerge from a void, and they don’t operate in isolation. Clocking in at 630 pages, The Origins of Totalitarianism is hard to recommend flippantly, but it does give pause to think carefully and slowly about the instruments of racism that imperialism inherited, evolved, and passed on. Since the traces of such technologies and discourses of race still inflect our current moment, it might have been valuable for the German Historical Museum’s exhibition to address some of these aspects of Arendt’s work more closely.