Shakespeare travelling

If your interests lie with the postcolonial, Shakespeare might seem like an unlikely port of call. Or rather, he might seem representative of a lot of the things a postcolonial approach would be interested in working against. He could, for instance, represent what needs to be removed in calls to ‘decolonize the university’: a dead white man with a Eurocentric view of the world whose literary representations are underwritten by racism and misogyny. In this essay, I want to think through some of these facets of Shakespeare that warrant critique from a postcolonial perspective, but also consider the enormously ambivalent ways in which ‘Shakespeare’ has travelled: the myriad meanings his works have made at particular moments in different contexts. I’m not so concerned here with Shakespeare the man, as I am with ‘Shakespeare’ in scare quotes: the works that have travelled through history to readers and audiences along various routes, and the array of meanings that have coalesced around them as they have made their sometimes-unpredictable journeys.

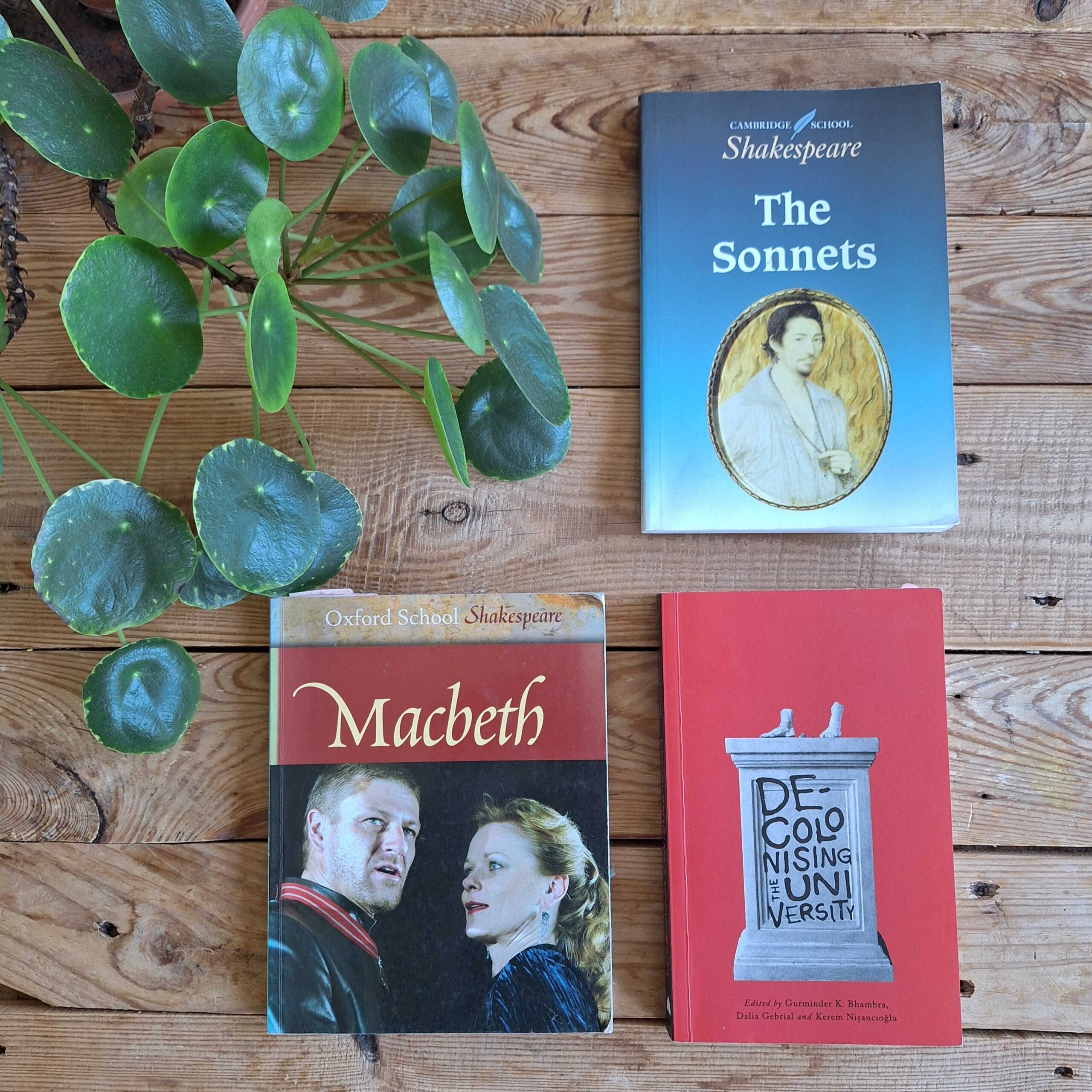

For English Literature with a capital L, it doesn’t get much more canonical than Shakespeare. He’s a feature of most English-language school syllabi; if you study English literature at university, you’ll be hard pressed to avoid him. If you aren’t directly confronted by screen adaptations or theatre performances, you could encounter him in TV shows where he’ll likely be referenced by characters to demonstrate how well-read they are. Shakespeare has become emblematic of a particular kind of literary value long presented as universal, widely celebrated for his ability to stage ‘universal’ themes.

But as many important thinkers have worked to demonstrate, the ‘universal’ is actually very particular.[1] Claims to universality might purport to speak for ‘humankind’ while only meaningfully taking into account a certain group of humans. In this way, they’ve been part of a conceptual machinery that glosses over difference as it consolidates inequalities. Reading Shakespeare in ‘universal’ terms might entail reading past many troubling particularities.

Historically, Shakespeare’s works were imbricated in British imperialism from early on. Born in 1564, the playwright’s life and career coincided with a period in which European encounters with those who would be made into Europe’s ‘others’ were proliferating at an unprecedented rate. As several thinkers have pointed out, there are good reasons to think about the early modern as the early colonial.[2] Columbus had departed on his fateful journey to the Americas in 1492, and England was involved in the trade in enslaved people by 1555, when John Lok brought five captured humans from Guinea to England. The East India Company was founded in 1600, when the playwright’s career was in full swing. It seems likely he was reading the reports of the journeys being undertaken beyond England’s shores that circulated. Othello, for instance, echoes Sir Walter Raleigh’s account of a voyage to South America in ‘The Discovery of Guiana”, when he recounts to Desdemona tales of journeys to lands peopled by cannibals and “men whose heads/ Do grow beneath their shoulders”. By 1600, London’s playhouses were receiving about 18-20 000 visits a week, and the representations they saw on stage were where many Londoners were getting their ideas of what people beyond their known horizons were like.

‘Shakespeare’ wasn’t just funneling encounters with otherness onto the Elizabethan stage. His work was also physically travelling outward with colonists: crew members of an East India Company ship performed Hamlet off the coast of Sierra Leone in 1607-8. By 1768, a volume of his works had become a must-have item in the luggage of an Englishman with expansionist intentions, as it accompanied Captain Cook’s Endeavour to the Pacific.[3] H.M Stanley (think “Dr Livingstone, I presume”)[4] recounts an occasion in 1877 in central Africa when the local population he was observing recognized the danger his note-taking represented to them and asked him to burn his notebook. Stanley preferred to set alight his copy of Shakespeare, which looked similar enough, thus saving his fieldnotes. Shakespeare was literally sacrificed to serve colonial knowledge-making of the ‘other’.[5]

In the colonial education system, ‘Shakespeare’ was part of an imperial architecture designed to establish the superiority of British civilization. Shakespeare became emblematic of an English culture that a colonial education coercively constructed as desirable. As Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, the famous author of Decolonising the Mind, put it acerbically, “William Shakespeare and Jesus Christ had brought light to darkest Africa.” In colonial contexts, fluency in Shakespeare might open doors for colonized peoples; it could function as a marker of prestige, and so enable upward mobility.

And even so, a postcolonial thinker like the Kenyan Ali Mazrui could come to the conclusion in 1967 that an education that taught Shakespeare imparted the skills that post-independence countries would need their leaders to have – albeit contrary to the intentions of the British.[6] Mazrui points to the instrumentalization of Shakespeare by Julius Nyerere, first president of independent Tanzania, who incorporated lines from Julius Caesar in early pro-democracy pamphlets, and went on to translate the play into Swahili. What does the appropriation of Shakespeare by a first president of a freshly independent post-colony into a local language do to the ‘Shakespeare’ that is emblematic of Englishness?

Shakespeare has been instrumentalized for anticolonial purposes at different times and places. Martinican poet, politician, and founding thinker of the Négritude movement, Aimé Césaire’s adapted/rewrote The Tempest – widely read as a Shakespearean rendition of the colonial encounter – in Une Tempête (1969). The play’s two enslaved characters, Ariel and Caliban, have long been contoured as different iterations of colonized subject positions: Ariel the acquiescent; Caliban the defiant. In Césaire’s rendition, Caliban is empowered, his resistance noble and just.

Twenty years later, another of Shakespeare’s plays was used to articulate a different relation to coloniality in its travels, as Othello was staged at the Market Theatre in Johannesburg in 1987. Almost paradoxically, this play of Shakespeare’s that is so famous for igniting discussions about its racism, was used to what were widely received at the time as anti-racist ends, as the public display of embodied on-stage desire played out between the Black actor John Kani and the white Joanna Weinberg held up a defiant middle finger to the apartheid government. In this performance – in a country that had repealed the so-called “Immorality Act” actually making such relations illegal just two years prior in 1985, but in which racial discrimination remained the governing principle – Shakespeare’s play was framed as protest art.[7]

Some of these instrumentalizations might depend on reading past particularities – and reading past particularities might be easier for some positionalities than for others. Instrumentalization might hinge on a universalizing gesture that is problematic in the ways described above. At the same time, making use of ‘Shakespeare’ to different ends has served some anticolonial projects at certain historical moments. For those of us embroiled in one way or another in English literature, he seems to be part of the inheritance. But it seems like it mightn’t be a static inheritance. Shakespeare is still travelling.

[1] See for example: Wynter, Sylvia. “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation–An Argument.” CR: The New Centennial Review, vol. 3, no. 3, Sept. 2003, pp. 257–337

[2] Loomba, Ania. Shakespeare, Race, and Colonialism. Oxford University Press, 2002.

[3] Neill, Michael. “Post-Colonial Shakespeare? Writing Away from the Centre.” Post-Colonial Shakespeares, edited by Ania Loomba and Martin Orkin, Routledge, 1998, pp. 164–85.

[4] David Livingstone famously embarked on a mission to find the source of the Nile, and went missing. H.M. Stanley was a journalist sent to the African continent to find the errant ‘explorer’.

[5] Greenblatt, Stephen. Shakespearean Negotiations: The Circulation of Social Energy in Renaissance England. University of California Press, 1988.

[6] Mazrui, Ali A. The Anglo-African Commonwealth: Political Friction and Cultural Fusion. Pergamon, 1967.

[7] Suzman, Janet. Who Needs Parables? Oxford University. 1995.