macht.sprache.: A discussion with Dr Michaela Dudley and Mirjam Nuenning (part 1)

On 19 May 2021, we got to hear from Dr Michaela Dudley and Mirjam Nuenning about their thoughts on translating politically sensitive language. You can find a recording of the event here. The event was a part of our macht.sprache. project, which is supported by the Berlin Senate, and which you can also check out here.

Mirjam Nuenning is a freelance translator of English-language Afro-diasporic literature, as well as founder of the Afro-diasporic kindergarten Sankofa in Berlin. After spending several years in Washington D.C., where she successfully completed studies at the prestigious Howard University – a Historically Black University), she now lives and works in Berlin. Her translations include “the things I am thinking while smiling politely” and “Synchronicity” by Sharon Dodua Otoo, and “Kindred-Verbunden” by Octavia Butler.

Dr. Michaela Dudley, a Berlin trans* woman with Afro-American roots, is a multilingual columnist, cabaret artist, keynote speaker and a lawyer. In addressing structural problems such as racism, misogyny and homo/transphobia, her focus is on diversity and language.

We’ll publish a transcript of the discussion in two parts. This is the first.

Dr. Michaela Dudley (MD): I’m a woman without a period but a hell of an exclamation mark. As a trans* woman, a Black person, a queer person, and a person in her 6th decade on this planet, intersectionality is anything but abstract to me. One of my approaches to language is trying to find tangential areas where we have these intersections, both with respect to the language I’m using in general and to translating it into other languages.

Translations is also a means of transcending things. But even within the course of one language, I find that language has the potential to emancipate. It emancipates us with respect to ignorance. It frees us. It allows us to dream, and dreams are of extraordinary significance because change begins with dreams.

On the other hand, chains, which bind us, iron shackles on our ankles and on our wrists – chains continue by virtue of dogmata and ideology. Dogma is a bitch, quite literally – a dog mother is a bitch. But of course when you use the B-word beyond the realm of referring to a canine, it’s insulting and misogynistic. But women also use it amongst themselves, and not only critically. When a man uses it, it certainly has a different connotation. When exploring language and what is politically sensitive, and what isn’t, we have to examine not only the content, but also the context in which it’s used.

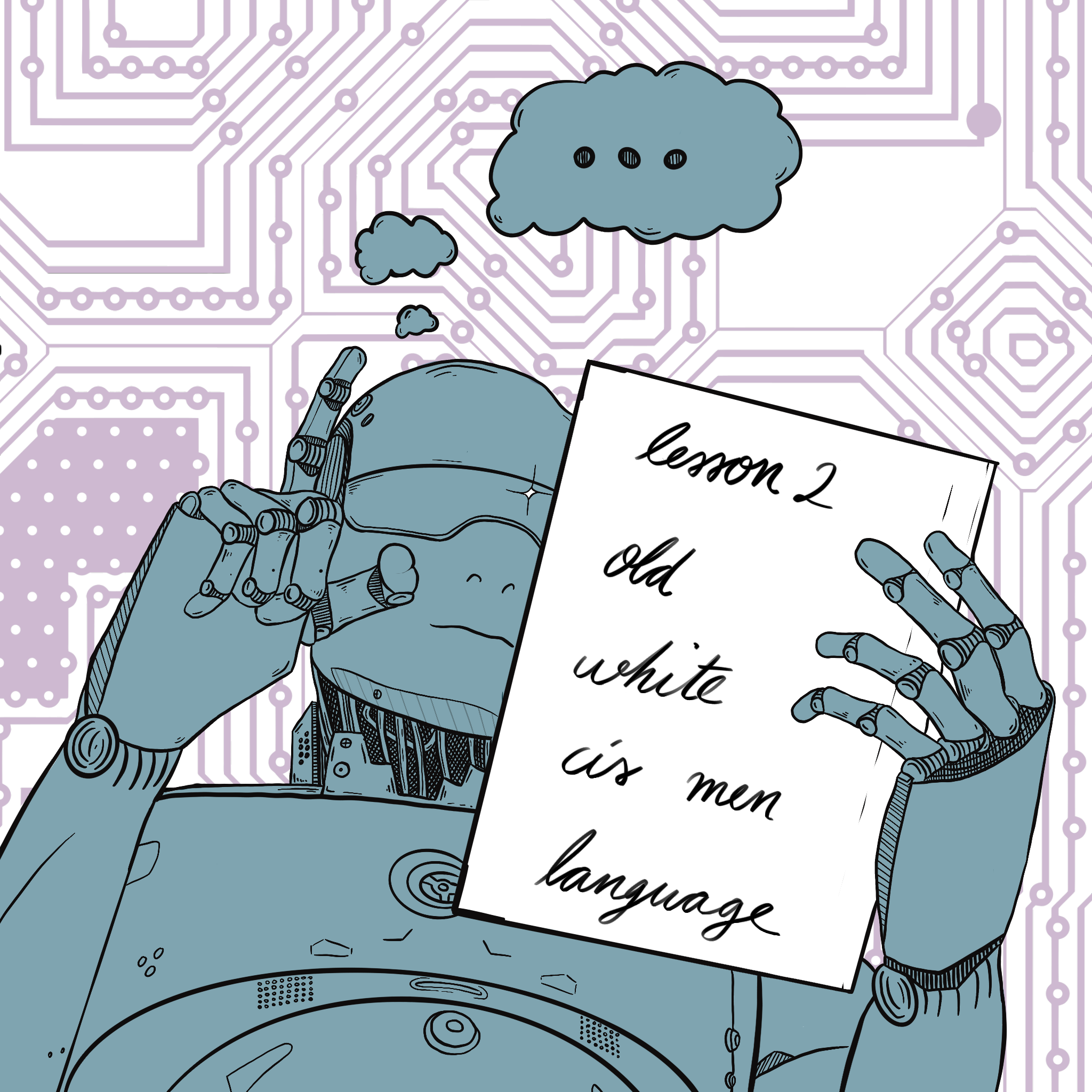

And why do I mention the sexuality here, when I speak of when a man enters a domain and uses that word? It has to do with the fact that men are inevitably involved. If we look back towards the rollback use of much politically and culturally sensitive language; if we look at the vitriol – it’s coming out of millions of mouths all over the world: “Why are you changing our language? Why are you trying to be so soft?” But it all comes from one basic source: that source is toxic masculinity. We also know toxic masculinity as male fragility on steroids. It’s part of the old, established, white, male, cis, heteronormative society. Anything suggestive of change, or restructuring, or modifying, is deemed to be a threat.

Spoken and written language is the most important means of articulating something. Much of the backlash is precisely because men and indeed women who are part of the patriarchy would prefer to hold on to that which they know. They’re threatened by a society that is diverse. I don’t say becoming diverse, because there were always aspects of diversity in our society. The question is if they were appropriately recognised and incorporated into society – and language plays an important role there . But recognising where that comes from, and the irony of it all (and this is why I use the term ‘male fragility’) is that they’re the ones being hyper-sensitive; they’re the ‘softies.’

Mirjam Nuenning (MN): I feel very blessed to be a part of this discussion and to be having this dialogue, because, as Michaela said, translation is transcendence, and translation needs to emancipate. It’s time that we look at the responsibility that comes with translation work, and at the value of shared experiences when it comes to translating, the importance of sensitivity to language and terminology — this is something that’s long overdue.

I love literature; I love Black literature. I feel very passionately about it because for me it has always served as a vehicle giving voice to my experience, my thoughts, my feelings; giving voice to the Black experience: the struggles, the triumphs, the resistance, the quest for Black liberation.

When we look at the status quo of some of the older translations of Black authors who were fighting against racism and for the liberation of Black people through their art; and then we look at the German translations that were reproducing the very racism that they were fighting against because the translators did not understand or share the experiences of the Black authors, they were not sensitive to language and terminology. A lot of what we saw was racist terminology. And I use the past tense, but this is very much still happening.

So the discussion that we’re having now is relatively new. We see racist terminology, a lack of understanding of culture. For instance, I read a translation where in the English original, the author wrote about about “Africans and Islanders”, and the German translation was “Afrikaner und Isländer” – Icelanders. And this is something that probably wouldn’t have happened with a Black translator, to whom it would probably have been clear that this person was referring to African and Caribbean peoples and not Icelanders.

Another example: a translator chose to not translate the term “brother” when Black men were talking to each other. But I don’t know any Black German men who refer to each other as “brother” in the English sense, unless they have an anglophone background – they would refer to each other as ‘Bruder’, especially younger generations. These are all things you have to be sensitive to.

We went from that to a time a couple of years ago when Black translators like myself were being asked to read over the work of white translators. At first, I thought: this is good, this is a shift. Then after maybe the third request, I thought: but it’s still the white translators who are getting the work and not the Black translators, and we’re having to basically clean up the mess. Something was still missing.

Fast forward to our current situation, especially since the debate over Amanda Gorman’s work [“The Hill We Climb”]: me and a lot of Black translators are receiving a lot of translation requests now, which is great, but I’m having to turn a lot of the requests down because I simply don’t have the time. I’m a single mother, I still have my day job to secure an income – and I share that experience with a lot of other Black translators. I’m part of a collective of Black translators who started organising about a year ago and we support each other. We talk about our struggles and they’re very similar. Traditionally, we didn’t get the translation jobs because we were not connected, we were not part of these networks. Now we’re receiving these requests, but we lack support. We still have multiple other responsibilities to juggle along with our translation work. I am very curious to see where this journey will lead us.

MD: On the issue of the post-Amanda Gorman approach – exactly around that time, I received a request from a German publisher to translate a book of essays by an Afro-American authoress. I was honoured, but at the same time I was a little bit sceptical because, for one, I was told it had to be done in a very short amount of time. The person from the publishing company said that she had just purchased the rights to publish the book in German, and she seemed more excited about the business of it than she was about the content of it. So I made some trial translations of a few pages – and she said: “It sounds too exalted.” It seemed to be her expectation that a Black woman would write from page to page in Ebonics, from the street corner. She could not seem to contemplate that this woman might use a higher form of communication.

I felt that she was trying to push me into a stereotyped corner, asking: “Would a Black woman really say that?” My response: “She did say that; read the language” This white German editor ended up asserting that she would understand Black English, including Ebonics, but Black English as a whole, at least as well as I would. So I turned it down. You see the struggle there where people still have stereotype points of views and regard that as a business model. Amanda Gorman was in the headlines, so it seemed a good time to bring out another book by a Black woman American author – without thinking that maybe we need a little more time.

So that they’re beginning to ask us to get involved in a broader frame is good, but for me, sometimes it’s just another form of tokenism: having a Black woman translate the book of a Black woman, but not actually wanting to take the time and see what’s being said and respect it.

Lucy of poco.lit.: In the foreword you wrote for your translation of Octavia Butler’s Kindred, which came out with w_orten und meer in 2016, you talk about positioned writing, positioned translating, and positioned reading. Could you talk about what you understand by these three prongs, and how you would locate your views in current discussions?

MN: Every translator, every reader, every writer is positioned in a certain way. I position myself as a Black woman. I view the world through the eyes of a Black woman. The world views me as a Black woman and treats me accordingly. And this shapes my experience; it shapes the way I move around the world.

I share parts of this experience with other Black people around the world. Of course, there are differences based on nationality, class, complexion, all kinds of things – but there is also a shared experience: what we call the Black experience. In that sense, I share that experience with other Black writers, other Black people.

A writer will also write from their own individual experience, and they will have an imagined audience in mind. The question is, which perspective is the writer writing from and who is that imagined audience that they have in mind? When the translator translates and interprets – because all translation is also interpretation – the work, they will translate from a particular perspective, and they also will have an imagined audience in mind. The question then becomes: who is that imagined audience, and is this translator able to relate and connect to the writer’s experience and perspective? Are they able to translate that; are they sensitive to certain nuances and codes and terminologies – such as the examples I gave earlier.

That’s where the Amanda Gorman debate comes in. It’s a long overdue discussion on really thinking about the importance of translation work and the responsibility that comes with it; as well as looking at who really was or is the writer and which perspective they are writing from, and who they are writing for.

Toni Morrison always said: I write for Black people and I’m not going to apologise for it. There is always a position that a text is written from, and there’s always an imagined audience that a writer has in mind, even though we barely think or talk about this. In terms of translation work, the question then becomes: Who has the knowledge, who has the expertise, who has the experience to interpret the original work.

This is why I’m glad that the debate has finally hit the mainstream, because this is something that people weren’t really thinking about before – and then you came across things like Michaela described. For example, Michaela, you talked about Ebonics. A lot of times, that’s translated as ‘broken German’, ‘gebrochenes Deutsch’, as with other forms like Creole or Pidgin – not respecting that these are actual language systems with roots in West African language and culture, and you can’t just make that grammatically wrong German and think it’s the same thing.

So, I’m glad that the discussion was finally sparked and that it’s hit the mainstream, but this is something a lot of us have been grappling with for years now.