Ecocriticism and Postcolonialism: When Land Remembers

Our Green Library readings with the authors Jessica J. Lee, Jennifer Neal and Inger-Maria Mahlke focused on how nature and the environment are negotiated both locally and in a global context. Whether their works were set in Taiwan, in the southern United States or on Tenerife, it became clear time and again that the topics – naming plants, nature as a fact-checker, control over natural resources – are of global relevance. Above all, a view through a postcolonial lens reveals colonial contexts and the continuation of power dynamics established by colonialism. The study of such literature falls within the scope of Ecocriticism. This essay is an approach to the potential of this concept in conjunction with a postcolonial revision of historiography.

Ecocriticism is a concept with an interdisciplinary approach that emerged in the United States to examine the different ways in which people imagine human relationships to nature and the environment, and how they portray it in books, films and works of art. Thematically, the field is quite diverse and can range from descriptions of idyllic landscapes, wilderness and animals – to pollution, apocalypse and visions of the future. Positions such as eco-feminism, ecomarxism or deep ecology fall into the broad field of Ecocriticism.

In part, the motivation for ecocritical work stems directly from environmental activism. Groups like Fridays for Future, Scientists for Future or Extinction Rebellion made the relevance of these concerns more visible in numerous protest actions in 2019. In addition to questions about the conservation of nature, connections between concepts of nature and culture also play a role, i.e. Ecocritics analyse how far justice issues affect different groups of people in addition to the environment in different ways – for example, people in the global North or South, people of different sexes, Black people, People of Colour, Indigenous or white people, etc. At this point, power emerges as a central component, which is also central to postcolonialism and its questioning of colonial continuities.

However, this interest in power dynamics and the ways in which different groups are affected by environmental concerns does not apply to all ecocritical works. In fact, just like current green, activist movements, the field has been criticised for its uncritical whiteness, and a blindness to racism and the positions of BIPOC – that is, Black and Indigenous peoples, and People of Colour. Just as Vanessa Nakate was recently cut out of an image in the media in a piece on climate activism, leaving only white Fridays for Future activists, ecocritical BIPOC voices are repeatedly made invisible. But they exist and their works deserve much more attention. One of them is the African-American Lauret Savoy, for whom writing about the complex intertwining of natural and cultural history is a way of seeking a sense of belonging in the ruins and shards of a world of conflicts small and large.

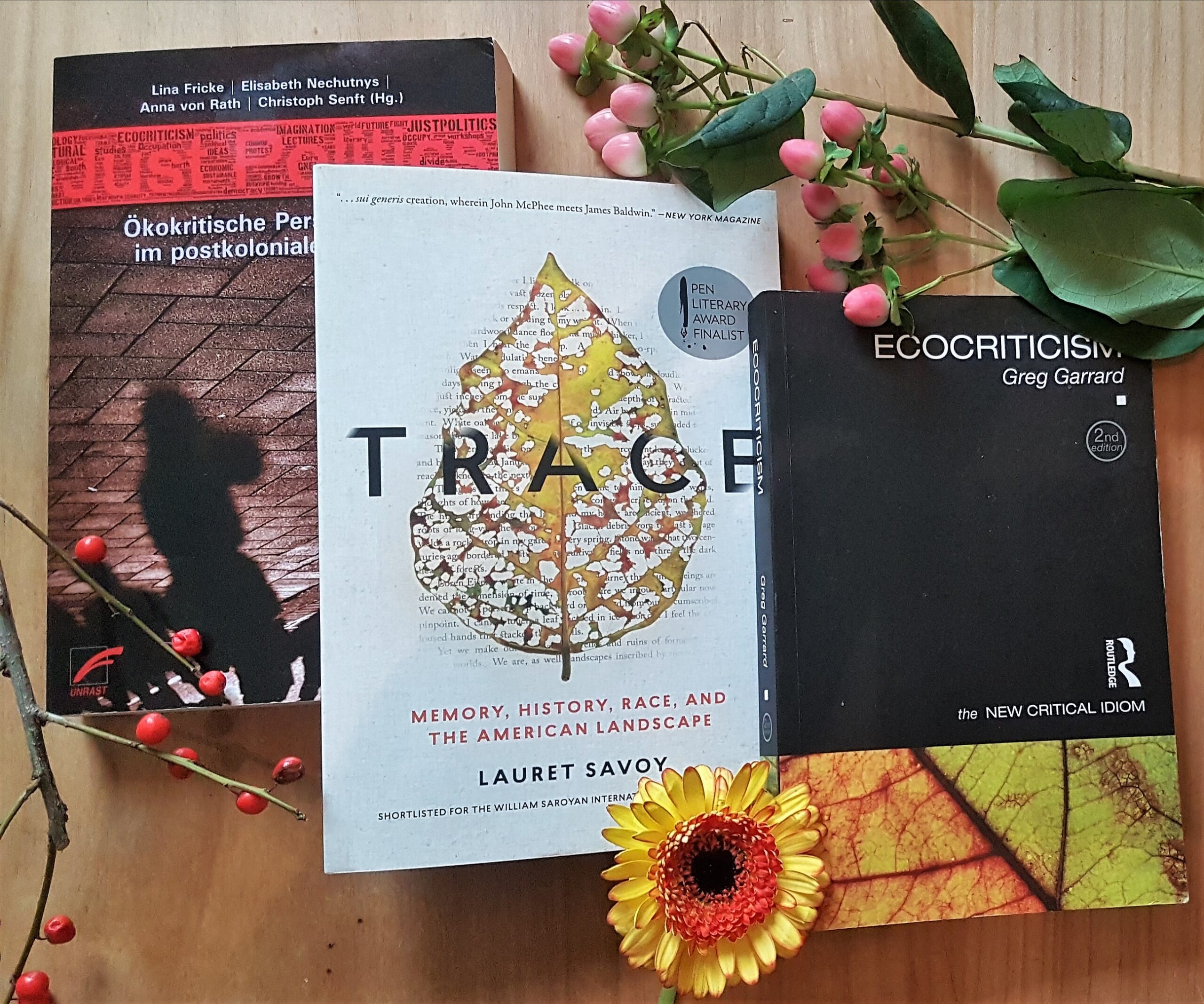

An analysis of various aspects – such as place names, official politics of remembrance, and the search for traces that open up a different perspective on both – based on Lauret Savoy’s book Trace: Memory, History, Race, and the American Landscape illustrates with particular clarity how productively postcolonialism and ecocriticism can be harnessed together. Savoy takes her readers on a journey through the USA to get closer to her own family history and to explore how the idea of race was inscribed in the country through human action. Her essayistic book combines detailed observations of nature with autobiographical anecdotes. She takes the gaps in her own family history as a starting point. As descendants of enslaved people, her parents could tell her little about their ancestors. With a few clues, Savoy begins to dig into history, thus gaining access to the land she was born in and the different people and groupings that have shaped it over the centuries. Savoy’s search is an attempt to locate herself in the country where her family has lived for generations, but whose traces are difficult or even impossible to trace.

In her search, Savoy repeatedly notes the extent to which racism is inscribed in the country, either through racist place names – which are so explicit that I will not repeat them here – or the deliberate overwriting of names by renaming them or omitting certain historical details. When Savoy visits the Walnut Grove Plantation in South Carolina, she learns on the tour that the white owners have been successful in making themselves self-sufficient. The subject of enslavement is simply left out. Another example are the names Ojibwa or Chippewa for Anishinaabe. The white ethnologist Henry Rowe Schoolcraft thought up the name Ojibwa for this indigenous people of the Anishinaabe and this word was later misunderstood, so that Chippewa became what in the 19th century found its way into a state treatise and thus became established. Lauret explains that

„In their place-making these newcomers [colonizers] not only set out to possess territory on the ground. They also lay claim to territory of the mind and memory to the future and the past.”

Trace (75)

In her remarks Savoy seems to make use of a common practice of postcolonial ecocriticism: With the help of the natural environment, she finds a new language to make the invisible visible. She tracks down stories by learning about rivers and lakes, by visiting canyons and cemeteries, and former plantations where people were enslaved. Savoy puts fragments together that still have to be characterized by gaps, but which nevertheless open up unexpected perspectives on the oppressed, the exploited and the displaced. In her essay “Common Ground? New Discussions on the Links between Post-Colonialism and Ecocriticism”, the scholar of American Studies Nicole Waller explains that some scholars locate the difference between ecocriticism and post-colonialism in their different interests: In post-colonialism, the interest lies in the study of displacement, migration and diaspora, whereas ecocritics are fixated on the relationship to land. Savoy combines both. She shows how powerful narratives about land and people blur, change and vary for their own purposes, but that traces for a different historiography still exist.

The work of making repressed or distorted fragments visible through a postcolonial and ecocritical approach can be understood as an invitation to self-reflection. A few months ago, after the brutal murders of Reyshard Brooks and George Floyd by white policemen in the U.S. and the subsequent Black Lives Matter protests, Jessica J. Lee organized a book club on Twitter under the hashtag #AlliesInTheLandscape to combat anti-Black racism in nature. In addition to content discussions on various books, including Trace by Lauret Savoy, Lee invited participants to reflect on their own actions and possible complicity. What people read and think, how they speak, and where they travel is shaped by social norms that sometimes seem invisible. But Trace shows that there are ways to intervene. Texts and places can be read through different lenses, because, as Savoy’s book shows, land remembers. It begins with questioning.