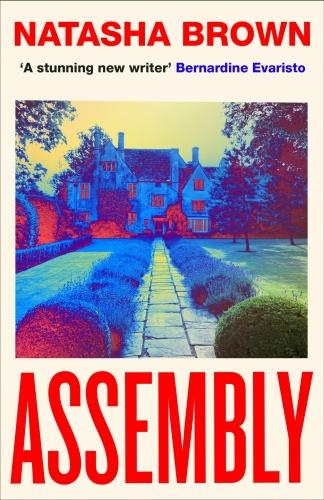

Assembly

As the title of Natasha Brown’s debut novel suggests, it amounts to a coming-together, an assembling. A Black British woman, the first-person narrator, attends a family party for an upper-class white family as their son’s partner. This celebration in rural England is the culmination of her inner dilemmas: has she made it or are her actions making her an accomplice to the racism she experiences? At this party, she makes up her mind.

Natasha Brown’s novel runs to just over 100 pages and consists of various, fleeting snippets of thought that gradually come together to form a hole-filled whole. The unnamed protagonist works in the financial sector, is promoted, has just bought a London apartment, and has invested her own money profitably. But this material success is marred by everyday racism and sexism, which make it increasingly clear to her how much she has to be bent and exploited to be part of this industry and environment. White male colleagues deny her competence when they tell her to her face that she only got her job because of the new emphasis on diversity. Male colleagues in similar positions demote her to coffee intern and demand secretarial work from her when they are too lazy to take on organizational tasks themselves. The protagonist plays along. She even consciously studies the behaviour of her white partner and her white friend Rach in order to acquire the necessary cultural capital, even as she thinks bitterly: “Born here, parents born here, always lived here – still, never from here. Their culture becomes parody on my body.“ Inwardly, she is consumed by anger at the unfair situation and feels additional guilt for trying to live up to a standard she will never be able to reach. I found the reflections in Assembly on the subject of complicity extremely interesting, and I have rarely read anything comparable.

Natasha Brown’s novel presents a downright unbearable lived reality, whose outward appearance is put in a completely different light by the narrator’s cool observations. It seems consistent that the protagonist sees her cancer diagnosis as a chance to break out of her constricted situation. She realizes at that moment that she can decide for or against her life. For her, it is not money that helps her escape injustice, but death. Since the book is told from the point of view of this one troubled character, it is clear that her way of thinking and acting is the result of very personal experiences. Her solution is certainly not one for everyone (and certainly not desirable). I know there are productive forms of resistance, but I appreciate Brown’s novel for the way it illustrates that exhaustion and disillusionment in the face of discrimination can prevail, and have serious consequences.

Order the book here and support us! The work behind poco.lit. is done by us – Anna und Lucy. If you’d like to order this book and want to support us at the same time, you can do so from here and we will get a small commission – but the price you pay will be unaffected.