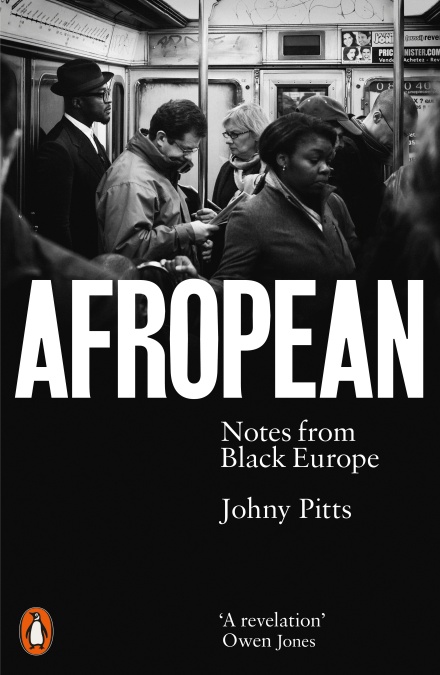

Afropean

When you imagine backpackers, who do you have in mind? Probably a white person, right? On his trip through Europe in search of the Black Diaspora, Johny Pitts found few travellers like him. Similarly thin on the ground for Pitts were role models within the genre of travel writing. He names just one direct precursor of his book, The European Tribe by Caryl Phillips. Phillips is a veritable idol for Pitts, due to the fact that his book, about a European journey some 20 years earlier, served to normalize the Black gaze by making white Europeans the objects of his observation. While Phillips writes about what it’s like to be among white people as a Black person, Pitts’ aim on his journey is to find Afropean spaces within the Europe that white people often define as homogeneously white – in other words, Black Europe, the people who make it up and its centuries of history.

With a relatively small budget that he has saved up over a long time, Pitts sets out on his own. He notes that the modest budget sets the framework for the trip, and thus also for the book: Pitts travels mainly in Western European cities with a short detour to Moscow. But this by no means indicates that there are no Afropeans in eastern or rural regions. Overall, I had the feeling that the book, despite its almost 500 pages, could have been even longer, because getting to know the different places from Pitts’ perspective was a pure joy. The impressions Pitts shares of the various places he visits are in turn amusing, moving, and critical, as he offers the insights of an interested listener and observer who consciously seeks challenging encounters.

Pitts often meets extraordinary personalities of the contemporary African community, such as the activist Jessica de Abreu in the Netherlands, the globetrotter Ibrahim – according to Pitts “the ultimate nomad” – in France, or Zap Mama in Belgium. The frequent references to musicians can certainly serve to put together a playlist for the perfect soundtrack while reading.

In addition, Pitts reports on exceptional historical personalities, i.e. those who long ago claimed space for Black presences in Europe. Pitts deals particularly with James Baldwin and Frantz Fanon, names African political leaders such as Nkruhma or Lumumba, and he criticizes Mobutu. In their own ways, each of these men plays a role for Afropean identity. Though he also mentions May Ayim, I would have liked to learn more about the long tradition of Black feminism and Black queer spaces in Europe. Especially in Germany, active Black self-organisation is closely related to feminist contexts.

Despite this small objection, it was a real pleasure for me to read about the city I live in, Berlin, from Pitt’s Black British perspective. He wonders about the left-wing scene as he accidentally ends up at an Antifa protest, where the all-white protesters adopt Bob Marley’s music. The demonstration is a terrifying affair for Pitts. Nevertheless, he concludes that the merit of Antifa is that at a time when the right is trying to make racism hip, it is making young white people enthusiastic about anti-fascism and anti-racism. The Afropean finds Pitts in a falafel store in Friedrichshain and in YAAM, the Young African Art Market.

Ultimately, the book relates how the Afropean is not necessarily a physical place, but is to be found in the echoes of European colonialism, that is, in what is displaced by the white majority society. The Black presence in Europe is directly related to European colonialism and this history must be addressed in order to actively combat racism and marginalisation.

Order the book here and support us! The work behind poco.lit. is done by us – Anna und Lucy. If you’d like to order this book and want to support us at the same time, you can do so from here and we will get a small commission – but the price you pay will be unaffected.