Afrofuturism 2.0 – a legacy of W.E.B. Du Bois

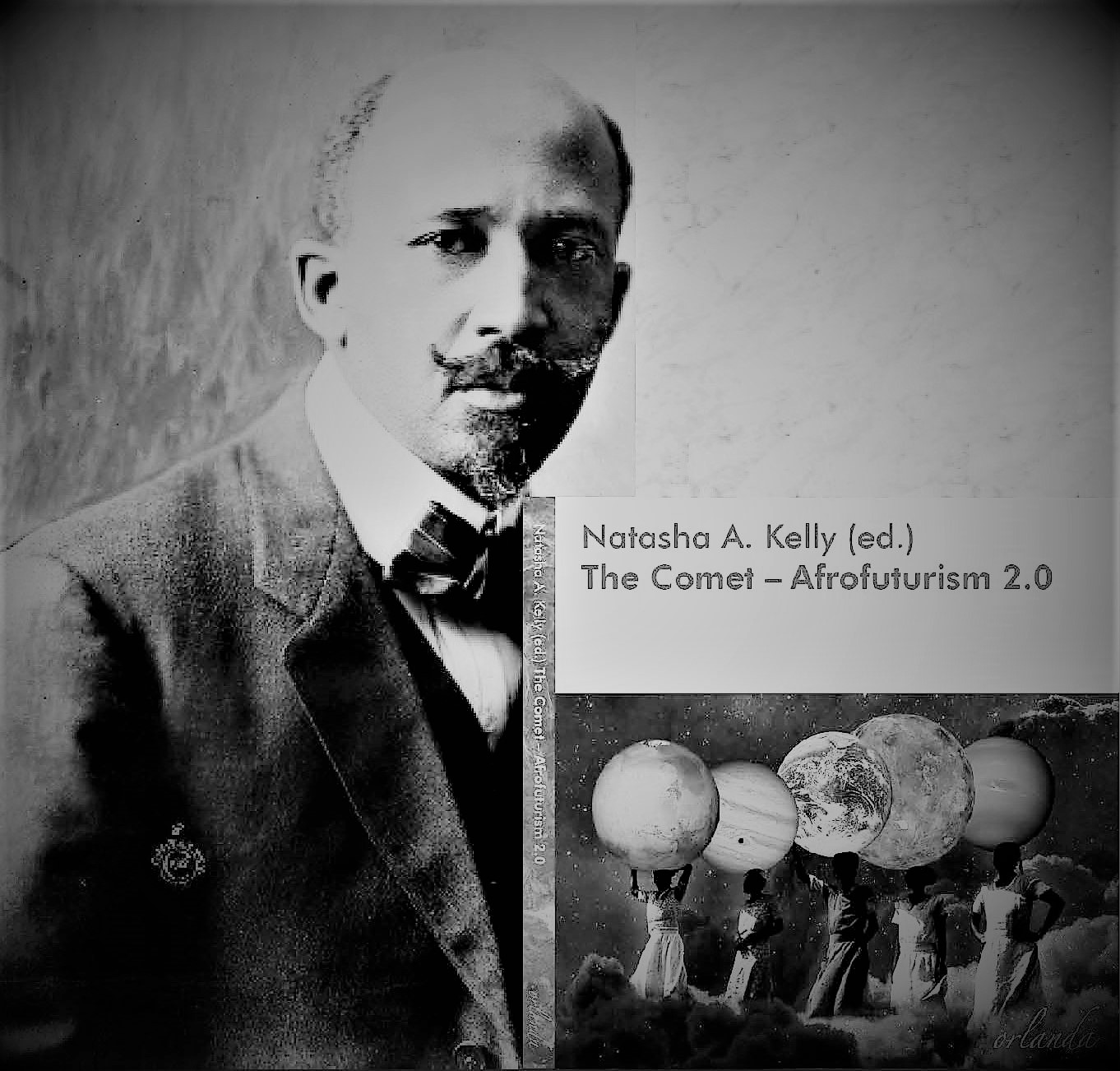

Alongside Afropolitanism, in which we have already published several essays (here, here, here and here), there are other future-oriented concepts that centre Africa and/or Blackness. One of them is Afrofuturism. The Afrofuturist movement strives for a space for independence and self-determination for Black people and rejects European universalism. The Afro-German academic activist and curator Natasha A. Kelly explains that Afrofuturism 2.0 builds on the theoretical and artistic legacy of W.E.B. Du Bois.

Afrofuturism emerges from the work of African and African-diasporic artists, musicians, performers, filmmakers and writers. Some well-known names include Octavia Butler, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Kodwo Eshun. The content and form of the artistic work often represent experiments with temporality, for which technological novelties are sometimes used as a starting point – such as spaceships or novel communication methods – as well as actual, current problems. The question is where this experimentation can lead: which paths might lead towards a world without racism, and what might that world look like?

In 2020, Natasha A. Kelly published the anthology The Comet – Afrofuturism 2.0 (Orlanda Verlag), which, in various contributions, documents the event she put together at the HAU Berlin in 2018, The Comet – 150 Years W.E.B. Du Bois. Kelly explains at the outset that she realized that there could be no new wave of Afrofuturism without Afro-Germany. Transnational connections have always been central to the Black German Movement, because the Black German community is relatively small compared to the USA or the United Kingdom. This is partly due to the fact that Black people were declared stateless and persecuted during the Nazi era. Since the 1980s, there has been an increase in Black self-organization in Germany, to which transnational influence and exchange have contributed significantly. The African-American Audre Lorde, for example, gathered Black German women around her when she was teaching at the FU Berlin and supported them in writing their own stories and developing a political terminology for their experiences.

Following this tradition, The Comet – Afrofuturism 2.0 works at the interface between Germany and the Anglophone world. All contributions to the anthology, which is designed like a museum catalogue, are available in both English and German, and the analyses of contemporary R&B music, comics, superhero movies, etc. can best be described as parts of global bridge-building efforts for an explicitly political, Afrocentric movement.

The book builds on the legacy of the renowned scholar, activist and journalist W.E.B. Du Bois (1868-1963), who also built bridges between continents – in his thinking, but also through his biography. For example, the native-born American studied at the then Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin (now Humboldt University) and moved to Ghana towards the end of his life. Kelly explains that Du Bois – probably without knowing it – was instrumental in developing the genre of Afrofuturism. The book The Comet – Afrofuturism 2.0 thus appropriately begins with Du Bois’ short story “The Comet”. Kelly translated this story from 1920 into German for the first time, and at what has turned out to be an eerily appropriate time.

When Du Bois wrote the story, the western world was trying to recover from the “Spanish flu”. Especially in times of Corona, it is spookily fascinating to read how thinkers imagined, almost exactly a century ago, that a pandemic could bring opportunities to change the status quo in the long term. Du Bois’ story was published shortly after the Red Summer, the period in 1919 when white people in the USA repeatedly committed acts of racist violence, up to and including lynching Black people. The year 2020 is most clearly marked, next to Corona, by the #BlackLivesMatter protests which were catalysed by the police killings of George Floyd and Rayshard Brooks. But the “Spanish flu” did not succeed in breaking down racist power structures, and even today it seems as though Corona, at least initially, strengthened anti-Asian racism. In the western media, there were also already suggestions to test a vaccine against the virus in Africa. Although a pandemic affects the entire world, the way it is dealt with is determined by established power structures – and possibly serves to magnify them. I am confident that the current situation will be dealt with artistically in astonishing and enriching ways. The question that the Afrofuturist movement suggests is: What are Black artists for (as opposed to only opposed to)? What vision of the future is created by the present, which in part seems like a variation of the past?

The Comet is a story, which describes how the destruction of the world as we know it allows the Black protagonist to be considered human by the few surviving white people. Destruction and its potential for change are thus the starting point for Kelly’s anthology. Karina Griffith writes in her contribution: “Thinking about comets not as a place or thing, but as a space- or thing-holder, helps to position the African Diaspora as a cosmos that can bear collective thought, experience, and agency” (42). In its entirety, the book offers a sometimes very abstract overview of important and pioneering political thinkers of the Afrofuturist movement. In order to read and process what it has to offer, I would therefore recommend taking your time. Du Bois’ work runs like a connecting thread through the entire book; his theory serves the contributors as an entrance ticket to various areas of the Afrocosmos.

Alexander Ghedi Weheliye, for example, refers to Du Bois’ call to imagine being Black acoustically. In The Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois frames his argument with sorrow songs, songs of lamentation that he describes as amongst the most important achievements of the USA, and as giving access to the landscape of the Black soul. Weheliye works through how contemporary R&B music can be understood as a direct descendent of these sorrow songs. The music stands as resistance – in form of sound – to the institutional disregard for Black life in white majority societies.

Afrofuturism has an almost infinite scope in how it wants to enable Black people to dream. African and African-diasporic history and experience is central to Afrofuturist thinking. The contributor Molefi Kete Asante emphasizes that only those who know themselves can produce their own creative visions of the future without merely imitating examples from others. In this sense, Afrofuturism invites people of African descent to think creatively and freely about the impossible.

In many ways, the Afrofuturist discussions of Kelly’s book seem to me to be far more radical than Afropolitanism. Afrofuturism here refers entirely to Black people and global networks between Black communities. Afrofuturism was never made for white people, although everyone may be able to go into the future together. In the Afro-future, according to Kelly, people will certainly not be colour-blind, but they will understand differences as a source of creativity. Afropolitanism, in a diffuse way, is much more conciliatory in its focus on negotiating different positions and accommodating behaviour. Political scientist Achille Mbembe argues that Africa should be a force in its own right alongside the other forces in the world, but he thinks that pan-Africanism and other race-focused movements have had their day. All those who are involved in creating African culture can be understood as Afropolitans – including the Asian Diaspora on the African continent and European settlers. It is a controversial attitude that strives for reconciliation, which certainly cannot yet exist from the Afrofuturist perspective represented in Kelly’s book.

But Afrofuturist perspectives are diverse and, according to Kelly, require an intersectional approach. The Comet – Afrofuturism 2.0 ends with a discussion on Afrofeminism in the Afro-future between Kelly, Sheree Renée Thomas, Karina Griffith, Priscilla Layne and Florence Ifeoma Okoye. Even the Afrofuturist pioneer Du Bois does not get off scot-free. In their conversation, the women discover that Du Bois was a gatekeeper who excluded women, and a colourist. The visions of the Afro-future of Kelly’s interlocutors make clear that they each have their own particular passion projects – a future free of hierarchy, a future that focuses on healing, or young people. Finally, though, the question posed by Molefi Kete Asante remains: Will there be people at all to experience the future?